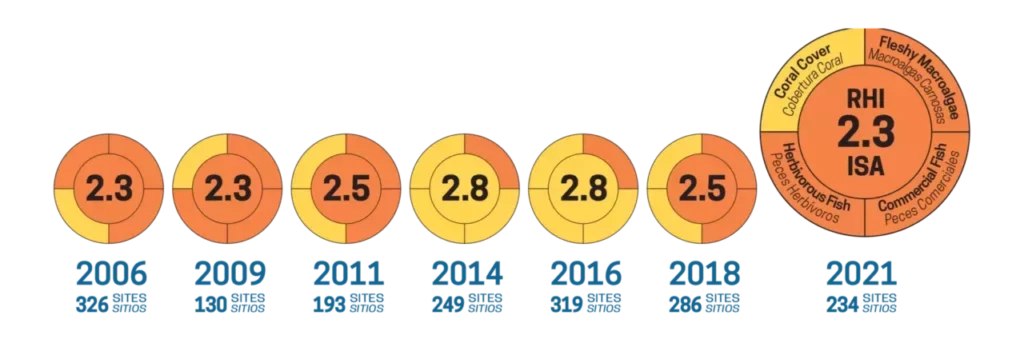

June 6, 2022: Lacking fish, Mesoamerican Reef health declines again to 2006 “Poor” levels

MESOAMERICAN REEF — A preliminary report released today by the Healthy Reefs Initiative (HRI) finds that reef health across the Mesoamerican Reef (MAR) has again slipped – reaching the same “Poor” rating that was reported in 2006—the first year the Reef Health Report Card was issued. Data were collected by 77 surveyors from 36 organizations from June to December 2021.

The Reef Health Report Card uses four indicators to understand changes in reef health over time: coral cover, biomass of herbivorous and commercial fish species, and fleshy macroalgae cover. Tracking changes in these indicators allows HRI researchers to evaluate which are of greatest concern at a given site as well as across the MAR as a whole, and how to approach solutions for restoring reef health.

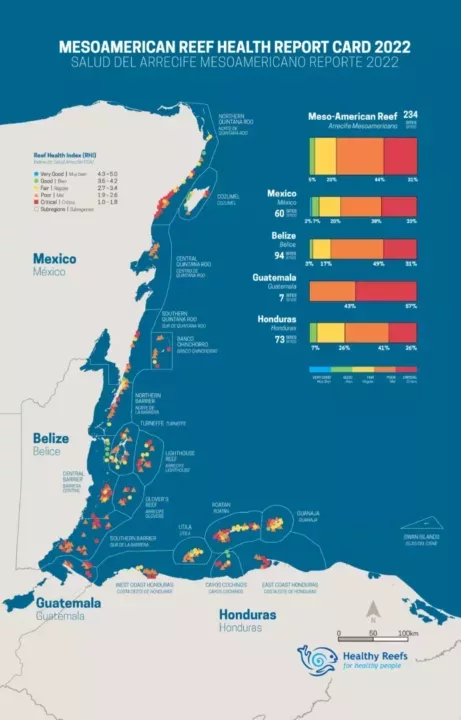

The majority, or 44 percent, of the 234 sites in Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras used to produce the Report Card measurements are ranked as “Poor”. The number of sites ranked as “Critical” has also doubled since the last report, reaching 31 percent of sites measured.

HRI researchers found only one site ranked as “Very Good,” in Cozumel, Mexico. This site has been fully protected from all fishing for decades, and it shows: the Cozumel site’s grouper and snapper biomass is over five times greater than the regional average. Additionally, only 12 sites (5 percent) were found in ‘good’ condition across the whole MAR.

Fish surveys covered about 140,000 square meters of reef in 2021; over 64,000 fish were counted. Groupers and snappers again had the greatest declines since the last report and now rank in critically low abundance across the MAR. Only 55 of the fish counted in the 2021 surveys were of the larger grouper species, and only 12 of these groupers were actually even large enough to reproduce.

To understand the scale of the loss of fish biomass across the MAR, consider a sports analogy: basketball. During a game, a typical 400-square-meter court has 10 adult humans running around. However, in an equivalent court-sized area of reef, we only have about 2 small grouper/snappers swimming around. But since the Report Card actually measures biomass, here’s another analogy: if each basketball player weighed 98 kg (216 lbs), the basketball court would hold about 980 kg (2,160 lbs) of human biomass. The Mesoamerican reef-court, as it stands today, only contains about 2 kg (4.4 lbs) of snapper and grouper, in human terms this would be equivalent to about 2% of one player – like one left foot. “It’s an empty court, said Dr. Melanie McField, HRI Director.” We’re literally dropping the ball.”

The low abundance and small size of commercial and herbivorous fish reveals a critical need for increased fisheries protection and management, primarily by a rapid and sustained increase of fully protected areas—as well as an increase in enforcing those protections.

“In the last five years we have lost all of the progress made in improving reef health over our first decade of collaboration, which culminated in the overall “Fair” score measured in 2016,” said Dr. McField, who is also a Smithsonian coral reef scientist with over 30 years experience working in the region.” Real protection needs to be absolute, as does our resolve to enforce it. This is a problem with a direct and feasible solution – one that will provide social and economic benefits, in addition to improving reef health.”

Across all sites, the largest gap to close to attain a “Good” ranking is in commercial fish biomass, which requires a 142 percent increase to indicate a healthy reef status. Next is a 77 percent reduction in fleshy macroalgae cover; then an increase of 49 percent in herbivorous fish biomass. Live coral cover across the MAR study sites is in the best condition, requiring only a 5 percent increase for sites to attain a “Good” status.

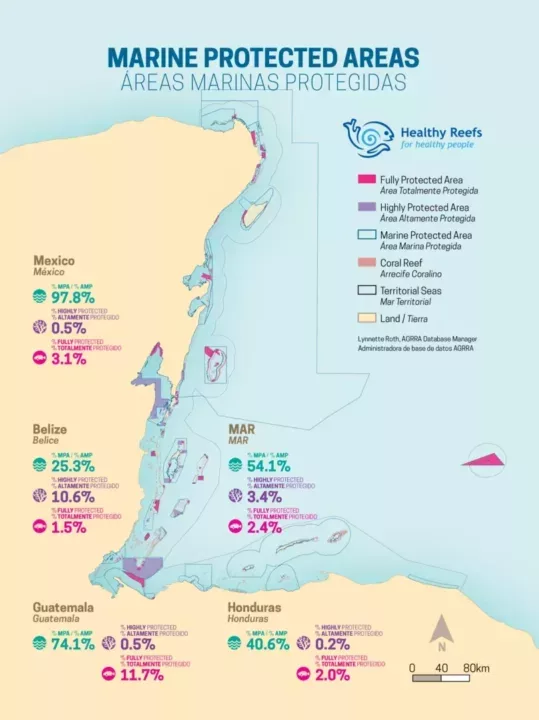

“We talk a lot about Marine Protected Areas, and allocate considerable financial resources for their management,” McField said. “However, when you look closely at the regulations in most of these zones you find that the fish are not fully protected from fishing. Globally, there are many calls for increasing marine protection, including recommended 30×30 (which is 30% highly protected by 2030). We have recommended putting 20 percent of the sea under full protection from all fishing in every Report Card we have produced over the last 15 years, in order to replenish populations within these zones, as well all of the other fished areas.

The MAR countries have designated over 50 (MPAs) that cover over 50 percent of the MAR territorial waters. Most are actively managed. But most of the MPAs still allow fishing – only 2.4 percent of of the waters are in full protection, far short of the area required to replenish fish stocks. “We are eager to study the reef response and hopefully record the recovery of fish populations in Guatemala, after declaring our first fully protected reef area in the amazing Cayman Crown reef in 2020” added Ana Giró, HRI’s Coordinator for Guatemala.

“We can fix the lack of fish in part by revising the zoning regulations within these existing MPAs to increase the area of full protection to at least 20%—meaning no fishing, including ‘catch and release,” McField said.

“This cannot happen without active enforcement, and a supportive community of stakeholders, including the fishers themselves, as we have done with the Alliance Kanana Kay, where fishers are designating and helping enforce some of the fully protected zones”, said Mélina Soto, HRI’s Mexico Coordinator.

“If we had placed 20 percent of the MAR under full protection 15 years ago when we first recommended this action, the region would now be reaping the benefits of more productive fisheries, improved reef health and increased tourism value in the fully protected zones,” McField said.

In addition to the challenge of faltering fish populations, we know that global climate change and disease outbreaks will continue to affect our corals, while nutrient pollution continues to fuel macroalgal proliferation. We also need increased efforts to improve water quality, control coastal development, increase herbivory and better understand coral diversity changes; all of which will be further discussed in our full 2022 Report Card, planned for September.

Source: Healthy Reefs Initiative Press Release – June 6, 2022